This is a series of flash interviews with people I admire, people who are doing something—anything, a lot of things—for the Earth. These folks walk the walk, each of them in their own way, using their own unique skillset. They dedicate their energy, their time, and their hearts to a crucial cause: the preservation of this precious planet we call home.

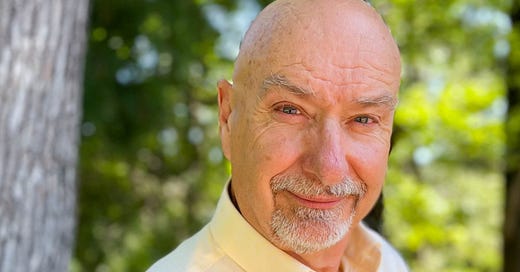

For longer than long, Rick Huffman’s name has been synonymous with all things nature-based in his native South Carolina. He’s an environmental designer by trade, but Rick’s love of native plants and his seemingly endless energy have fueled a deep well of care for the Earth.

“Someone has to speak for that which cannot speak,” he says. “Nature needs us to be the voice.”

In 1996 Rick co-founded the South Carolina Native Plant Society. That same year, he started his own firm, Earth Design, which specializes in sustainable landscapes of indigenous flora. I met Rick quite a few years ago, when Earth Design created and installed an all-native landscape on my small city lot. I don’t live there anymore, but I fondly remember the lovely rain garden their team created to solve a drainage problem.

Rick’s main volunteer involvement is with the S.C. Native Plant Society: 13 years as president, frequent speaker for monthly meetings, serving on the board statewide and for his local chapter. But he also has a long record of serving on the boards of other local environmental efforts, and he has won multiple statewide awards including Environmental Educator of the Year, the Governor’s Award for Environmental Awareness, and Upstate Forever’s Volunteer of the Year. His extensive resume also includes co-founding the National Native Plant Coalition and the Southeast Exotic Pest Plant Coalition.

Several months ago, the Conservation Voters of South Carolina honored Rick with a Lifetime Conservation Award. The prestigious award recognizes someone with a long record of leadership in protecting, enhancing, and restoring the state’s land, air, and water. He also recently has been nominated as a Fellow of Landscape Architecture, an honor he says he is “geeked to be recognized by my peers nationally.”

Here’s what Rick shared with me about his lifelong passion for preserving our natural treasures and the “all-out, urgent effort” he wants to inspire in us all.

Rick, please tell us about some of your early experiences in nature.

I think our earliest experiences are foundational in connecting us to nature. We are born connected; we are sensory creatures, instinctually curious about nature. Exposure and experiences focus on our perspective. It’s like a lens through which we see and connect to our natural world, frame by frame. Layers shape our perspectives, opinions, and values. Nature sense, I like to call it. My earliest memory is when I was ten years old, my mother sent me to live for the summer with her kinfolk near Andrews, North Carolina. The Winfreys’ homeplace was perched deep in the Nantahala Mountains, five miles from a paved road. They had no running water or electricity. They grew what they needed. I worked hoeing potatoes and getting water from the spring—sweetest water ever. At the time, I questioned why my mom would send me to the middle of nowhere. But now my nature sense connects those memories of the lush green world and the simple lifestyle, the smells of the air on cool summer mornings after a rain, the outhouse, and the sounds of birds. All those memories stick with me. On inspection of my life and mission, it seems each experience is the process of awakening.

How did those early experiences shape your relationship with the natural world?

Those early immersions in nature began to shape an appreciation for nature that fueled a desire to learn as much as I could about plants, systems, and biological cycles. Starting in the nursery industry, my understanding of plant sciences and the natural world opened a new appreciation for nature. Early on I could see a world of industrial, artificial landscapes and creeping asphalt. I felt a responsibility to change that paradigm and rethink our relationship with our land, landscapes, wildlife, and water. I felt that as we grow and build, we can do so in harmony and as stewards. I say yes! Through my professional work with Earth Design and conservation, I learned how to create substantial, ecologically sound designs. In the ’90s, the “green build” initiatives began and as a new graduate of the University of Georgia with a degree in landscape architecture, I was on it. My conservation advocacy, with the South Carolina Native Plant Society and the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources Heritage Trust, has helped me learn more about the canvas on which we sign our signature every day. Those experiences provided a lens through which to see the natural world and also the drive to meet the challenges of creating ethical land use.

How do you connect with nature now … through your work or leisure or both?

I find nature everywhere I go: in cracks of sidewalks, vacant lots, graveyards, open fields, deep woods, rivers, and streams. Yet true serenity, true solace is seeing the balance of nature, feeling the ancient call of systems and cycles. Knowing plants and plant communities is like a superpower. Through landscape architecture, that superpower becomes applicable to solving issues and building a more sustainable world. In my leisure time, it’s through the South Carolina Native Plant Society: teaching, leading, developing partnerships, and getting conservation done. My professional career is working across disciplines such as the U.S. Green Building Council, American Society of Landscape Architects, Conservation Voters of S.C., and SCPRT—all providing the platform for sound ecological design, using an understanding of hydrology, trophic systems cycles, plant communities, and fungi as a basic catalyst to heal and restore. Sustainability is actionable through ecologically sound design principles that balance art and science, like we have practiced at Earth Design for 28 years. In the ’70s, I saw the damage we had already inflicted on the planet. Connection and remembrance provided a drive, a thirst to gain knowledge so that in some way I could mitigate impacts.

What are your biggest fears for the future of our planet?

My biggest fear is also my biggest hope. I fear that coming generations will not be able to see the same ecosystems and special places, to hear the songbirds my grandfather heard. Greed, ignorance, denial, and inaction, even knowing what we know, is a slap in the face to future generations. But that’s what conservation is about: battling, struggling, scratching and clawing to save this, preserve that, hold bad actors to account, and educate the public. That inspires hope for land preservation, ecosystems, and biomes as keys to a living, thriving planet. Teaching fundamental ecology and making earth education standard for young generations will help, as will teaching land ethics as fundamental to building a society that values ecosystem services. I helped to launch a program using Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac to inspire environmental awareness in 7th graders.

What is your biggest hope for the future of our planet?

It’s the young people. Growing up, my generation was not exposed to knowledge about nature or climate or how the environment works. So we have not made good decisions. Everywhere I go around the state, seeing young people working in science, advocacy, and conservation jobs, I feel impressed and hopeful. This younger generation has been more exposed to the science of nature, and their values reflect a commitment to change how we operate.

I have always reached for education. Environmental education creates land ethics. It comes back to values. If we do not find the ethics and moral will to do the hard things, we will not. Education must be global and directed to the everyday person. It must start early. Children’s values start with education. We teach people how to compete in the global economy; let’s also teach ecosystem services, and create generations of bright young minds that can figure out how we heal and respect the global ecology. Our planetary health is teetering. We need an all-out, urgent effort. A billion dollars is a small down payment on the future.

Thank you, Rick, for being a Champion of Nature!

I really liked this interview Jeanne. Rick makes a lot of great points on connecting with Nature. I appreciated his point about finding Nature wherever he goes, too. I think that is a great way of connecting with Nature. This way of looking at Nature and connecting with Nature makes it much more accessible to people. Thanks for sharing.

What a great quote: "Someone has to speak for that which cannot speak. Nature needs us to be the voice.”